|

|

|

| BOOK REVIEWS Terri Hendrix Adam Carroll and Stayton Bonner |

|

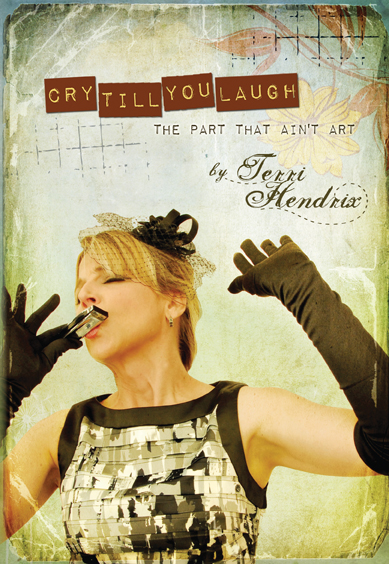

Cry Till You Laugh — The Part That Ain't Art |

Terri Hendrix’s fans know just how well the woman can write. But in addition to the many, many fine songs she’s written over the past 15 years, the pride of San Marcos, Texas, has been waxing poetic for nearly just as long in a series of e-mail newsletters she calls “Goat Notes,” named for the scraggly beasts she helped care for on her late friend and mentor Marion Williamson’s Wilory Farm. The goats and the farm have factored into Terriworld ever since, including songs like “Get Your Goat On,” merchandise and the name of her own label, Wilory Records. Hendrix’s “Goat Notes” are not your run-of-the-mill, “Hey, here’s what I’m doing, here’s where I’m playing, buy my t-shirts” newsletters, although there is some of that in them. They tend to be deeply personal ruminations on a metaphorical theme or topic, usually inspired by a seemingly mundane occurrence in her corner of the world. Hendrix takes these newsletters to their natural progression with her first book, the 185-page Cry Till You Laugh — The Part That Ain’t Art, a well-written and engaging companion piece to her latest album, the jazz-inflected Cry Till You Laugh. The book collects both new writings and older (though often updated) “Goat Notes” musings on topics ranging from singing bullfrogs (really, it’s about how she protects her voice) to Obama’s election (it’s about the optimism she felt and her parents’ contrary sentiments), along with song lyrics, photos and a section devoted to how you, too, can become a hard-working, beloved, fiercely independent DIY artist. She calls that chapter “The Part That Ain’t Art.” It’s not only a nifty how-to on everything from getting copyrights to getting copy written about you in the press, it’s a dramatic illustration of how wrong-headed the record labels that spurned her became shortly before they started their long teeter on the precipice — and how much easier it is for a talent like hers, with determination and elbow grease, to make music her way without some pinhead in a suit telling her to sound more like Taylor or Lady A. As interesting as it is to hear this stuff from the horse’s, er, goat’s mouth, Hendrix’s most riveting passages deal with her career-impacting battles with epilepsy and her parents’ declining health. These are candid and deeply personal, yet Hendrix’s sunny personality and storytelling gifts shine through. In 2005’s “Brainstorms,” she offers her first memory of going into convulsions, and what followed. “I lay shaking underneath a thin cotton blanket as the doctor stood over me, tapped a clipboard with his pen, and splashed me with an ice-cold dose of reality,” she writes. “He informed me, in a nasal drawl, that I had epilepsy ... I was barely conscious, worn to the bone and my tongue felt like it had been through a meat grinder.” Hendrix’s writing is rarely esoteric. She opens up about difficult subjects, like her fears and insecurities, in the same straightforward manner that makes her songs such seemingly simple wonders. In 2009’s “Change and the Exploding Toilet,” she recounts how a particularly unpleasant plumbing experience taught her to laugh when, well, she felt like crying. The incident occurred as problems with her parents’ health and behavior were mounting. “But thinking back on that moment when, while standing in shit, I chose laughter over anger, love over fear, and resolve over crying, I realized that I’d changed,” she writes. “It was my nature, in times like that, to start ‘spinning off’ or ‘freak out.’ But I had done neither. A calm, like a quiet, silver lake came over me.” Speaking of change, I do hope she makes some changes to the layout of the book if there’s a second printing. Presently, the columns of type are too wide and it’s difficult to read the words closest to the inside margins because they are too close to the spine. This probably saved money on printing by keeping the page count down, but it’s a pain. You have to bend back the pages and run the risk of weakening the spine and loosening pages. But you don’t want to do that. You want to read every word. [Note: Terri Hendrix confirms that a second printing is already in the works with these issues corrected.] — DOUG PULLEN Doug Pullen covers arts and entertainment for the El Paso Times. |

Old Town Rock N' Roll: Stories About Music |

Twenty bucks might seem a bit steep for a wafer-thin paperback book of fun-sized short stories, even shorter, journal-type snapshots from the road and the odd poem or song lyric. And to be honest, it is; at 62 double-spaced pages (with a handful of cartoonish, black-and-white illustrations), Old Town Rock N’ Roll: Stories About Music is a quicker read than your average Reader’s Digest. But that little quibble aside, from a quality over quantity perspective, this collaboration between Texas songwriters Adam Carroll and Stayton Bonner is genuinely delightful. There are no co-writes here; Carroll and Bonner each contribute their own pieces, which are identified at the end by their respective initials. Read a handful of them, though, and you can tell straight away who wrote what. The entries by Carroll, the more seasoned songwriter of the two, all have the Texas beat-poet wit and almost Forrest-Gumpian wisdom of his best songs, with equal measures dry humor and a kind of bittersweet nostalgia couched in deceptively casual character sketches: “She was a waitress working right off the Flatonia exit on I-10. He was an old man who came in every day to drink coffee and look at her and scratch his old head.” Bonner, a songwriter/journalist (Texas Monthly, GQ, Outside) who previously wrote The Bookman, about writer Larry McMurtry’s side career as a rare book dealer, has an even sharper eye for details — sometimes maybe a little too sharp (“He opened the beer and took a long pull. It mixed with the cigarette and coffee residue stained on his gums.” Eww.) But overall, his vignettes are every bit as enjoyable as Carroll’s, with his “Playing for Tips,” a painfully funny account of a particularly grueling, thankless opening-act gig in the Forth Worth Stockyards, standing out as one of the book’s most engaging chapters. With writing that good, you really wish Carroll and Bonner had sat on Old Town Rock N’ Roll (which shares its title with Carroll’s last studio album) until they had twice as much material; not just to better justify its price tag, but because what’s here leaves you wanting more — in the best sense. — RICHARD SKANSE |